Hebrew Lettering and Jewish Mystical Art: A Look at David B. Wolk’s Scriptural Paintings

12 Feb2014

What is it about the Hebrew lettering, and its written word, that makes it so dominant in Jewish mystical/abstract art today? In a parallel vein to artist Mel Alexenberg, who proclaims post digital art requires the inspiration of creative Judaic thinking, painter David Baruch Wolk believes that contemporary abstract painting has true meaning only when contending with intellect and the written word. According to Wolk, where abstract expressionism ends, visual words begin. A look at Wolk’s conceptual process provides a glimpse into the function of Hebrew lettering and their words in the visual aesthetics of the mystical Jewish painter.

What is it about the Hebrew lettering, and its written word, that makes it so dominant in Jewish mystical/abstract art today? In a parallel vein to artist Mel Alexenberg, who proclaims post digital art requires the inspiration of creative Judaic thinking, painter David Baruch Wolk believes that contemporary abstract painting has true meaning only when contending with intellect and the written word. According to Wolk, where abstract expressionism ends, visual words begin. A look at Wolk’s conceptual process provides a glimpse into the function of Hebrew lettering and their words in the visual aesthetics of the mystical Jewish painter.

When it comes to incorporation of texts, Wolk, with the rest of the Jewish mystical movement, is in parallel existence with the general contemporary visual art world. The formal inspiration is identical. Text begins being incorporated by neo-Dadaists such as Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns who use cultural symbols to find meaning in their paintings. Post-war artist CY Twombly incorporates text as a sort of personal encrypted communication. Ruscha, pop artist from the beat generation, is famous for text-only paintings inspired by these artists. Words contribute to conceptual art as well, as in contemporary African American artist Glen Ligon who uses text to tackle concepts of race and culture. Wolk too, seems to continue a formal contemporary tradition: “Where Jasper Johns left off,” Wolk says, “there I started.” But, the use of text in Jewish Mystical Art takes on a very different meaning.

Take the last Heichal Shlomo show called My Soul Thirsts from the Jerusalem biennial, displaying contemporary mystical Jewish artists. There, Hebrew words were predominant, in works by Yossi Arish, Israel Rabinovich, David Louise, Metavel, Asher Dahan, Yudit Margolis, Tal Levi, Daniel Flatauer, David Freidman, Avraham Loewenthal, Baruch Nachshon, and of course, David Baruch Wolk.

In contemporary art, words contribute to a personal or cultural story; amongst the mystical Jewish artists text is sacred and represents spiritual exaltation. For example, Ruscha uses text as a celebration of pop-culture, marking modern irreverence for art. But Wolk uses words to transform visual arts into an elevating inspiration. Using a medium in danger of being idolatrous, from the biblical perspective, Wolk’s paintings document the mystical process of becoming closer to G-d.

In contemporary art, words contribute to a personal or cultural story; amongst the mystical Jewish artists text is sacred and represents spiritual exaltation. For example, Ruscha uses text as a celebration of pop-culture, marking modern irreverence for art. But Wolk uses words to transform visual arts into an elevating inspiration. Using a medium in danger of being idolatrous, from the biblical perspective, Wolk’s paintings document the mystical process of becoming closer to G-d.

Words are part of sacred texts and have deep meanings. Amongst religious artists, they are not expressions of a culture but rather of a greater existence.

Words are part of sacred texts and have deep meanings. Amongst religious artists, they are not expressions of a culture but rather of a greater existence. Wolk describes the incorporation of Hebrew text into his painting as a process of moving beyond shape and into meaning and intellect. Words, he says, are the DNA of creation and are spiritually revealing. Wolk insists that any artist who wants to make his art holy will incorporate the Hebrew lettering.

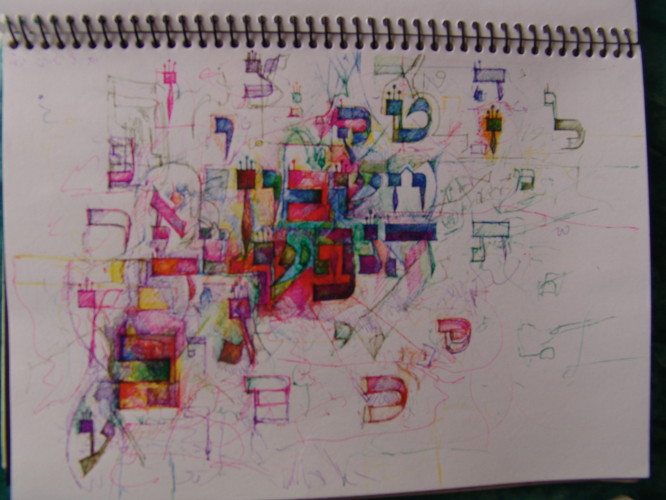

In contrast to other scriptural arts, Wolk has a unique visual way of working through a question, never letting go of meaning and intention. Returning to painting after working as a Torah scribe, he asked himself, “If the Torah changes lives, then what am I doing making art?” After years of concentrating on holy texts, focusing on forming letters embodied with meaning, he had to discover a way to incorporate such a process into art making to inject purpose. Visual impacts are powerful and sometimes dangerous. With these questions disturbing David Baruch Wolk’s conscience, he felt a need to transform the visual arts into a positive influence. As seen in the texts chosen for inspiring his earlier works, the paintings ask if art is permissible as something spiritual and meaningful and they work through the answer.

In contrast to other scriptural arts, Wolk has a unique visual way of working through a question, never letting go of meaning and intention. Returning to painting after working as a Torah scribe, he asked himself, “If the Torah changes lives, then what am I doing making art?” After years of concentrating on holy texts, focusing on forming letters embodied with meaning, he had to discover a way to incorporate such a process into art making to inject purpose. Visual impacts are powerful and sometimes dangerous. With these questions disturbing David Baruch Wolk’s conscience, he felt a need to transform the visual arts into a positive influence. As seen in the texts chosen for inspiring his earlier works, the paintings ask if art is permissible as something spiritual and meaningful and they work through the answer.

An important part of Wolk’s answer is the incorporation of Holy Text. Other mystical artists usually incorporate words into the illustration of a phrase or concept. Wolks paintings, however, progressively break down holy phrases and letters into purely visual form. The letters are his paintings. One does not need to use particular words, he says, the actual Hebraic forms are holy enough.

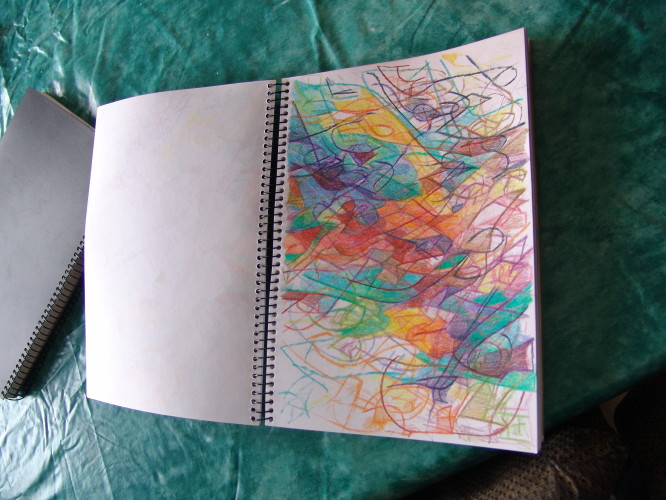

In scribe work, the negative space is as important as the positive space of the letter formation. This teaches about the combined existence of the written letter, whose meaning is clear, yet hints, to a less understood space existing outside the letter. It seems the more Wolk’s paintings accept themselves as “allowed to exist” within the Torah valued world, the more the letters’ physical representations integrate into the abstract space. It is as if letting go of known forms suddenly enlightens the eye to the presence of hidden shapes. I am sure that for Wolk this is a very deep metaphysical lesson.

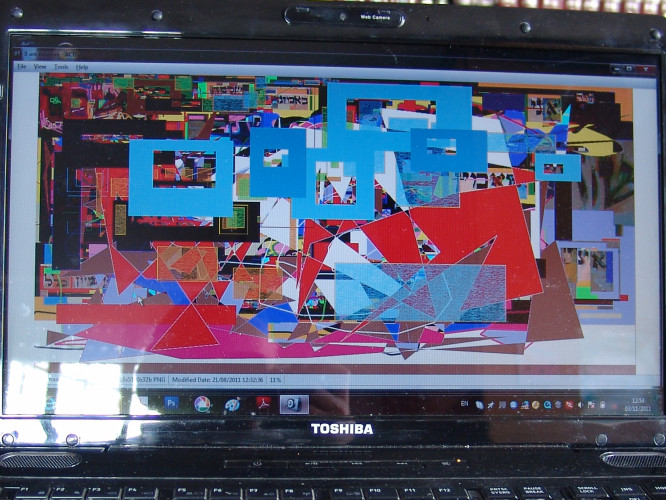

Wolk recently advanced his word refinements beyond sketches and painting and into digital manipulations. On the digital screen he liberates literal form, transforming basic letters and word inspirations into many layers of shapes and textures. The digital paintings mark the movement from statements of literal textual inspiration towards scriptural meanings integrated into abstract forms.

Wolk recently advanced his word refinements beyond sketches and painting and into digital manipulations. On the digital screen he liberates literal form, transforming basic letters and word inspirations into many layers of shapes and textures. The digital paintings mark the movement from statements of literal textual inspiration towards scriptural meanings integrated into abstract forms.

David Wolk believes that abstract art needs holy letter structures for spiritual meaning. Culture is ephemeral, and Torah changes lives. Jewish art must be based on the holy text, he says. I am sure other visual expressions can be spiritually moving. But for men of the book, text is essential.

- In: Featured Artists

- Tags: Israel, Painting