Jewish art spans city with ‘Sacred Words, Sacred Texts’

31 Oct2013

by Jonathan Maseng for JewishJournal.com

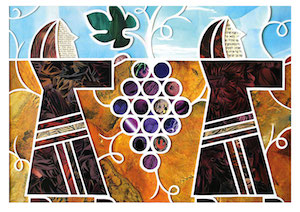

“Rebel Spies,†by Isaac Brynjegard-Bialik, mixed media, 2013. On loan from Scott and Gayl Gluck.

“Sacred Words, Sacred Texts,†which officially opened Oct. 6 with a reception at AJU, is an exhibition that celebrates Jews as a People of the Book: Torah, Talmud, Midrash and sacred poetry are all explored through various media by more than a dozen Jewish artists from the L.A. area. It was curated by Anne Hromadka, Sara Cannon and Georgia Freedman-Harvey.

A second reception — this time beginning at HUC-JIR and spilling over to the nearby USC Hillel — took place on Oct. 13, featuring a wide range of styles and forms, from a very traditional, literal sculpted Torah by Soraya Sarah Nazarian, to Will Deutsch’s instantly recognizable drawings, to a video installation by Jessica Shokrian featuring accompanying spices that guests were invited to sniff in a sort of avant garde Smell-O-Vision.

Hromadka said that one of her main motivations for the exhibition was to ask the question, “How are Jewish artists thinking of ourselves as keepers of the book?â€

She continued: “In thinking of ‘Sacred Words,’ I wanted to think about not just the words that we speak to each other, but what are some of the holiest words ever spoken in our tradition? And those are often the words spoken from God to us.â€

Hromadka highlighted the work of artist Andi Arnovitz, a beautifully constructed sculpture made of Hebrew text featuring colorful flourishes that depict the battle between the houses of Hillel and Shammai, the circa first century BCE rabbis whose heated debates helped shape much of religious Jewish law and custom.

“The scrolls that make up the house are actually copies of pages from the Talmud,†Hromadka said.

She also spoke about a piece by Iranian artist Krista Nassi, who immigrated to the United States in 2006 after living in Iran post-revolution. The piece, a bold painting featuring sharp contrasts between darkness and light, and the text of the Shema, was apparently a personal one for Nassi.

“She lived in Iran during the Iran-Iraq war,†Hromadka said. “Whenever there was shelling … her family would gather in one space in the house … and they would huddle. And what were the words they would say to comfort themselves? The Shema.â€

Among those in attendance were participating artists Melinda Smith Altshuler and Isaac Brynjegard-Bialik. Altshuler, speaking briefly, highlighted her use of found objects in her work, which she credited to her father being in the scrap metal business when she grew up. He’d bring home “wonders†that she couldn’t help but love. Altshuler described her work, which included a piece that made use of old record sleeves, as being “like the anti-text, because they really have to do with addressing recording, which is what the written word is also, but with visual materials.â€

Brynjegard-Bialik went into more depth about what the concept behind “Sacred Words, Sacred Texts†means to him.

“What I’m trying to do is tell stories,†he said. “I’m very much into our narratives, our stories as a people. Most of my work is informed by biblical stories. And I always say my work starts with text. Maybe it’s a portion from the Bible, maybe it’s something from Talmud, maybe it’s a myth, as with the golem story.â€

Brynjegard-Bialik’s beautiful pieces, which weave in images from comic books to create mythic takes on Torah and the Jewish experience, breathe new life into the often tired art of paper cutting.

“It’s all about revisiting these texts, revisiting these stories, revisiting those things that inform us as a people, and trying to make sense of them,†he said. “The text becomes ours to own and to struggle with. What I try and do is put that struggle on the page.â€

Read the full article >>

- In: Exhibition Reviews

- Tags: Art as Midrash, California, Installation, Jewish Artist Groups, LA, Painting