Challah Baking Creates Unexpected Printmaking in “The Bakers Brand”

13 Jun2014

Artist profile by Yehudis Barmatz.

Motta Brim: Born in Jerusalem, 1959. Lives and works in Beitar Illit.

The life of a Hassidic man, family and community oriented, is quite domestic. Often this is overlooked by the world at large. But this introverted reflection and domesticity inspired Motta Brim’s new and original works in a recent show at the Jerusalem Artist House, called “The Bakers Brand,†a series of markings on baking paper left over from Hallah baked for the Sabbath. “Every Friday I am in the kitchen, cooking for the upcoming Sabbath.†Motta explains. “One of the activities I love to do is Hallah Baking.â€

Motta Brim is inspired by the beauty of life from a passionate Hassidic perspective. Raised in Meah Shearim, the heart of the ancient Jerusalem ultra-orthodox community, Motta is a traditional Hassidic Israeli in all ways expected. As many in his generation from ultra-orthodox Jerusalem, he served a day job as a teacher of ultra-orthodox school children for twenty six years. He established his family in the newer ultra-orthodox community of Beitar Illit, on Jerusalem’s outskirts. What distinguishes Motta from other Hassidim is his call to the arts. “Even my mother,†he says, “saw me as a little different. When everyone else would normally be given the name Motty as short for Mordechai, she coined me the name Motta.†In his early twenties, he tells me, already a few years beyond his “Heder†(ultra-orthodox elementary school) years, he bumps into a childhood teacher. The first question the teacher asks is “Nu, do you still draw?â€

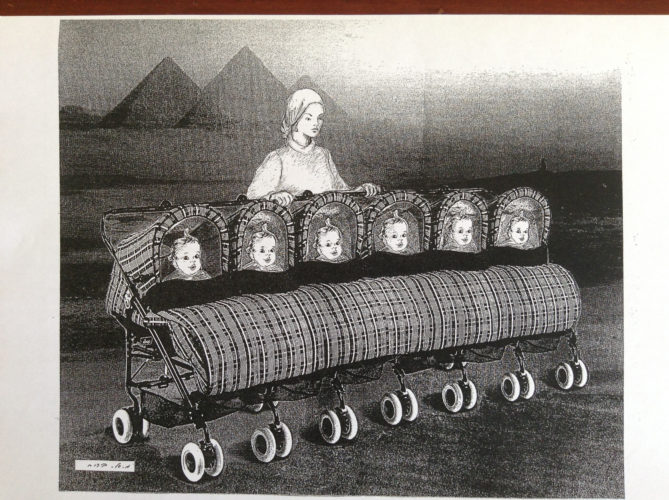

During the years as a teacher, Motta never ceased working as artist. The traditional attitude of “being born an artist†kept Motta painting shamelessly. He studied in the Jerusalem Painting and Sculpture school under Israeli artist Lillian Klapisch, and artists Joseph Hirsch and Jan Rauschwarger. As a school teacher, Motta could not resist using his talent to help the children visualize different stories from the weekly Parsha. He illustrated the forefather Jacob, blessing his grandsons, the Jewish mother of Egypt with six babies, and other such biblical scenes as a way to tell over biblical stories to the children. The parents of the school children objected to these drawings. They felt illustrations of biblical figures was irreverent. They took their objection to the late esteemed Rav Elyashiv, expert in Jewish Law. They never told Motta what his response was, but the parents left Motta alone. Out of curiosity, Motta made an appointment with the rabbinic leader himself. In an unusually long meeting of fifteen minutes, he shows his illustrations, and receives rabbinic approval to use them in his classes, on condition the imagery remains respectful.

For as long as he worked as school teacher, Motta has been a member of the Jerusalem Artist House. Motta is recognized amongst the traditional Jerusalem art scene. Amongst a list of other solo and group shows, a painting of his hangs in the Jerusalem High Court House. Five paintings were displayed in the Israel Museum show called “Local Pictures†(2001).

Motta will not be found sitting exposed on the street painting scenery, but rather in his studio, painting to the background of Hassidic music. (See on you tube “Aryeh Dehri†by religious radio host Menachem Toker). Motta’s subjects steer away from Jerusalem scenes, focusing inward into the home. His previous paintings are inspired by still lives and everyday objects, whose ephemeral use of color is fauvist in nature. “My paintings,†Motta said “are observational, though not needing to stick with reality. I have never considered them Jewish art, because to me ‘Jewish Art’ is Kitsch, but they are rather a natural choice from the items around me.â€

This is in contrast to the attitudes of many original Israeli Bezalel-School artists. The founder of the Old Bezalel of Art and Design encouraged his students to use ancient Jewish motifs in the making of a New Hebrew Art (Manor 2004). Many artists, who were European immigrants, such as post war Reuben Rubin (-1974), focused on still life and street scenes as symbolism for developing a uniquely Jewish and Zionistic art. An example is Shalom Sebba’s piece “Pomegranate†(1960). Motta, perhaps particularly because of his religious affiliation and Old Jerusalem roots, and perhaps as an artist in an era following the postwar Zionist efforts at creating identity, veered away from this style to a quieter, more personal traditional painting.

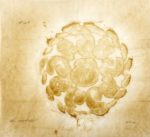

“The Bakers Band†is Motta Brims first series which could officially be called, by the artist, a Jewish subject. Collected over a length of two years the forms were discovered spontaneously and he framed them for his living room. Upon the encouragement of Israeli art critic Gideon Efrat, Aric Klimnik artist and owner of the Jerusalem Print Shop, Leon Klapp, and curator/writer Albert Suisa, he considered displaying the paper as art not just for his personal enjoyment.

No longer the previous quite self-portraits and interiors, these art works look deeper into the domestic life of a Hassidic Jew. Simultaneously a break from the traditional in art and a return to traditional roots, the forms take on Matisse-like sensuality and homage to ancient ritual. When Motta bakes he incorporates Hallah-baking traditions he remembers from his grandmother, including twelve piece Hallahs, the key shape Hallah, the round braided Hallah, all used as Kabbalistic rituals in accordance to the various cycles and holiday seasons of the year. The results are an abstract visual integration of feminine and male qualities within ritualistic and Kabbalistic life. These works are far from products of an obviously male artist, but rather reveal a purer complex domestic intimacy.

“The Bakers Band†is an honest return to Motta Brim’s roots while artistically taking a step forward. After years of painting simple beauties around him, and perhaps years of refusing to embrace the “kitsch,†as he calls it, of the Jewish symbolic mystical art, the foundation of Zionistic postwar era, his eyes are open to discover immediate beauty of everyday life. The discovery of the Hallah baking sheets as a printmaking technique rescued what otherwise could have been two years’ worth of trash. A sort of found and recycled art, a by-product of deliberation and intention of ritual, reveals an honest intimate experience of a Hassidic Jew.

I personally hope that Motta Brim continues with this inspiration, moving onward and inward to share with the world the aesthetics and sensuality of Hassidic mystic ritual.

Yehudis Barmatz-Harris is a sculptor, painter, and art therapist with a BFA in sculpture from Pratt Institute and a degree in art therapy from Seminar Hakibbutzim in Tel Aviv. Ever since arriving in Israel in 2009, Yehudis has researched, written and interviewed artists in her quest to discover her place amongst the quietly developing contemporary mystical art movement in Israel.

Image Gallery